There’s an almost symbiotic relationship between pigs and apple trees and oak forests, that dates back thousands, probably even tens of thousands, of years.

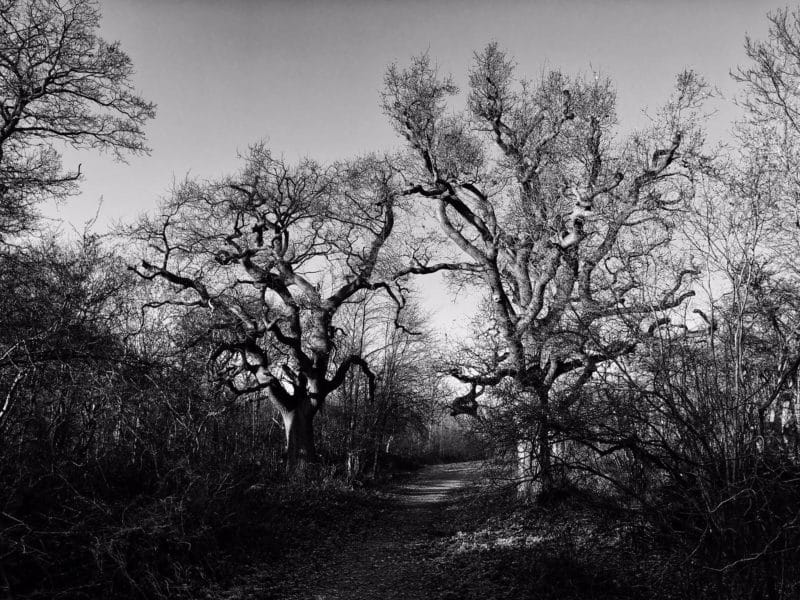

These great oak trees below are to be found in Brampton Wood where we walked yesterday.

It’s the second largest ancient woodland in Cambridgeshire, dating back at least 900 years. The first mention in the Doomsday Book records it as:

“…woodland pasture – half a league long and 2 furlongs wide”

It’s surrounded by a large earth bank which marks the old, traditional boundary and there are also several other minor banks and ditches inside, thought to be prehistoric field drainage systems. And here as in almost all the wooded areas of England, pigs used to be pannaged. Unfortunately, this practice stopped many years ago now, but I’m sorely tempted to ask if we can run a few pigs of our own through there next year…

Pannaging is an ancient right, kindly given to us poor commoners by those wonderful ‘nobility” fellows. It is still legal though and is actively practiced in the New Forest, although I’m not aware of any other large areas in the UK where the pigs are still regularly released, de herbagio like this, even though some 2% of the Welsh and English commons have live pannage rights listed. It’s likely though that canny local farmers in those areas will take advantage of oak trees on or adjoining their own property, even if they’re not legally practicing pannage.

After payment of a nominal £4 “marking” fee to the Forest Verderers, the pigs are let out by their owners (many of whom have had these inherited pannage rights handed down though generations over the past couple of hundred years) to eat the fallen acorns, occasional crab apples, chestnuts and beech mast (from the old English word “mæst”) that have accumulated, often in huge piles in mast years, on the ground, and, depending on the amount of food bounty found, can be left there for weeks.

The pigs have an, er, robust digestive system so can safely gobble as many acorns as they can stuff into their capacious maws at the same time, safely clearing the area for the ponies and cattle, also roaming in the forest, that often poison themselves whilst eating too many of the green, unripened, acorns. It’s an important “forest health” role; nearly 90 New Forest animals died, during what was apparently a bumper season for acorns, in 2013.

The pigs efficiently turn this food into the resulting prized “pannage pork”; it’s hugely popular (especially, naturally, with chefs), sells out often before it hits the butcher’s shelves, as the quantity available to sell depends on the availability of a suitable number of pigs, which depends on the quantity of acorns which in turn totally turns on the weather; but assuming all goes well, these will normally start appearing on the oak trees around the end of September. The pannage season officially lasts for 9 weeks, so the pork becomes available for only a short period around the end of November and early to mid-December. As only around 600 pigs are released nowadays, it’s obvious that this produce is going to be hellish expensive.

There’s an aptly named Pig Hotel at Brockenhurst …

…located in the middle of the New Forest, run by a well regarded chef, James Golding — who raises his own Saddleback and Tamworth pigs on site and that are slaughtered by his local butcher, Mr Bartlett — who says of this delicious, dark, British Ibérico-style ham:

“We always serve it medium and always very simply, to enhance the really excellent flavour. The second you put it in your mouth, you know the flavour is something special. As the pigs have been left to roam, the fat content seems to be a little less and the meat slightly darker and drier, with a more concentrated flavour. It’s extremely ‘porky’.”

“I always say that a happy pig is a tasty pig. It’s like every seasonal food; it’s not around all year and should be enjoyed when it’s available and at its best.”

And apples? Pigs love ’em. Interestingly their seeds contain a substance called amygdalin which is a cyanogenic glycoside. This amygdalin can release hydrogen cyanide in the stomach, causing discomfort or illness and is, albeit rarely, even fatal. That said, usually the seeds are swallowed whole, so the risk of this toxin being absorbed is little to none; it is simply digested whole and then excreted. Which means our pigs may get an aching stomach through over-eating but no long term ill effects; and who hasn’t suffered through that, eh?

Get to ’em boys (and girls)!

These crab apples were fallen from trees close to the house yesterday. Again, no pigs around at the moment to take advantage of this food-source but…