If a menu isn’t in a language I’m able to — however slowly — stumble through, with at least a vague sense of how 3 or 4 words in the description sound maybe slightly familiar, how then to choose a meal that I hope will be good (or even great)? Often, just pointing and taking pot-luck (see what I did there?) works really well. It’s a fun leap in the dark, even if at the end of the meal, you’re still not quite 100% sure what everything was that you’ve put in your mouth. Sometimes, once or twice, I gotta say, I’ve regretted my choice…

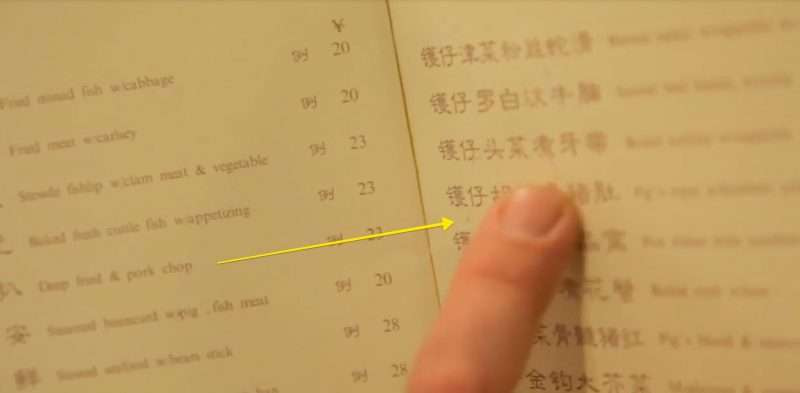

Today I picked up a rather excellent tip from Harley Spiller, a New York resident, who, for the past 40 years, has been collecting Chinese restaurant menus, amassing a collection numbering now more than 10,000 (I do like me a monomaniacal collector, don’t you?) who suggested looking closely to see those menu items that had a blue Biro tick or ink marks next to them — those were, he said, “the ones that the waiter had pointed to with his pen to recommend”.

I kinda think that after all these years and all these menus, that’s not a bad idea to follow. That, or learn some Chinese. Which actually is on my list of things to do…

I’ve recently found myself becoming more and more interested in diaspora food & by the immigrants and children of immigrants who’ve written so eloquently about these meals, the ‘traditional’ ones as well as those new ones that they’ve put together in their new country and their importance to their very identity, with some of them still feeling “strangers in a strange land”, some apparently completely integrated, yet still aware of how the food and the cooking had moulded them and their parents and grandparents.

I came across a film about the history of “General Tso’s chicken” (左宗棠雞, pronounced tswò), a sweet, spicy, deep-fried chicken dish to be found all over North American Chinese restaurants, one whose origin story is more than a little murky and mythologised.

The very wonderful guru of all things Chinese, Fuchsia Dunlop (and if you don’t already have at least one of her books, what even are you doing?)…

…posits that it only dates back to the 1930’s/40’s and was introduced into New York, via mainland China, Kuomintang forces and Taiwan, as a way to encourage white people to start using Chinese restaurants and pay to eat something that they’d be able to call “exotic” and congratulate themselves on their daring cosmopolitan palate but that one didn’t overly challenge their taste buds too much.

For what it’s worth, I think that sounds very likely.

And by the way, if you’re England based and you’d like a similar one of those cleavers she’s showing — without having to travel to Hong Kong to pick one up — she’s recommended buying from the See Woo company, based in London’s Chinatown.

There’s a long piece coming in the next day or so on some of these books I’ve been reading but, in the meantime, set aside an hour to watch this fascinating investigation.