At school I steered clear (in as much as this was feasible anyway in a school that thought a caning, regularly applied, was some sort of educational incentive) from the classics. Latin — taught by a man who, at least at the time, seemed to me to be as old, dried up, boring and archaic as the dead language he espoused — I gave up as soon as I could, in favour of French & German. Anything on Ancient Greece and Rome glossed over in a rapid sideways move to American & European history, courtesy of an ex-USAF Major called Dick Hoeren. My Latin is abysmal, my knowledge of Greek even less, so it was only today that I read of dinner tables in colonialist Raj era India described as a “hecatomb” via the hugely interesting “The Raj At Table”, by David Burton…

In ancient Greece, a hecatomb (UK: /ˈhɛkətuːm/; Ancient Greek: ἑκατόμβη hekatómbē) was a sacrifice of 100 cattle (hekaton = one hundred, bous = bull) to the Greek gods. See what useful information I missed out on picking up then, by my intransigence? Oh well, better late than never.

The implication of its use here of course being that the British masters had so much money that they could afford the waste involved in this display of any and everything edible from India, being laid out and left largely uneaten (although I imagine that the many poorly paid servants didn’t let much go to waste).

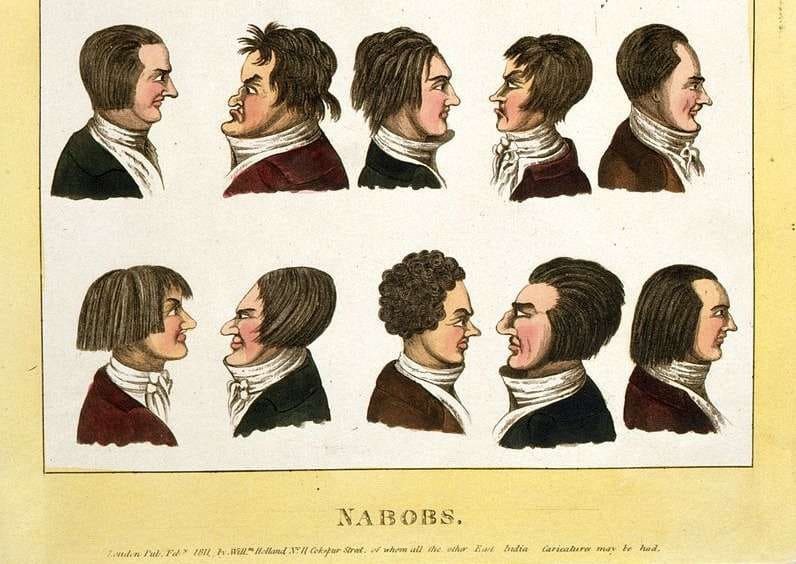

Part of an 1811 caricature of some ‘nabobs’, published by William Holland on 11 Cockspur Street, London

I read this quote about some of the nabobs in the East India Company:

Their migration was two-fold: migrating to India in the 1790s gave them access to power and riches through the East India Company; migrating back to Britain allowed them to translate that wealth into power within the British state.

Patronage and power, the latter of course then regularly abused:

That they had sprung from obscurity, that they had acquired great wealth, that they exhibited it insolently, that they spent it extravagantly, that they raised the price of every thing in their neighbourhood, from fresh eggs to rotten boroughs, that their liveries outshone those of dukes, that their coaches were finer than that of the Lord Mayor, that the examples of their large and ill-governed households corrupted half the servants in the country, that some of them, with all their magnificence, could not catch the tone of good society, but, in spite of the stud and the crowd of menials, of the plate and the Dresden china, of the venison and the Burgundy, were still low men; these were things which excited, both in the class from which they had sprung and in the class into which they attempted to force themselves, the bitter aversion which is the effect of mingled envy and contempt.

Thomas Babington Macaulay on the nabobs, in Critical and Historical Essays, 1848

The more things change…