Writer Jenny Linford’s @jennylinford “The Missing Ingredient: The Curious Role of Time in Food and Flavour” speaks to the centre-pole of any form of “cooking” (using that word in its very widest sense, that of in some manner or other, preparing an ingredient rather than simply grabbing whatever it is and then swallowing it), highlighting the importance of patience. Whether it’s the 4 ½ minutes for a perfect soft-boiled egg, the 4 or 5 hours to bring everything good out of a chicken-carcass stock pot, the kitchen-warming, overnight slow-cooked pork belly, the two or more years waiting for some cheeses to mature or even the 12 years needed to produce premium soy sauces; in all cases, time needs to pass by. Patience needs to be exhibited. And most particularly, this time lapse is required in the making of ferments. It’s an investment on your part or a “delayed gratification” (as I’m sure the economists would label it). But what do they know? Trying to dress up their version of modern witchcraft and entrails divining, into some sort of pseudo-science…

But I guess they’re right in this one, limited, instance (in the same way as a stopped watch is ‘correct’ twice a day, albeit totally fucking useless): such processes need a delay, a period of time for the microbial magic (and yes, it really does seem magical in the old idea of the word) to take effect. To go on to change fundamentally the structure, the taste, the smell, the feel, the look, ones’ ability to digest the food, yes, even the likelihood of you dying (or rather not) after eating the item you’ve chosen to ferment.

In the same way as Jonathan Swift was attributed in suggesting…

it was a brave man who first ate an oyster

…so I wonder who it was who first thought “let’s add some salt to this cabbage and leave it for 4 or 5 days” to produce sauerkraut or even longer, three or four weeks plus for a good kimchi? The kidney beans that first have to be boiled for 10 minutes to remove the toxic lectin protein in the skin or cassava, a staple food for over 800 million people. How many died of the cyanide in the latter, that needs 3-4 days soaking in water and then a similar course of boiling, to remove the last traces of that “smell of almonds” poison?

Who came up with the idea of inoculating rice with a mould, one aspergillus oryzae, to then get to kōji, itself ‘merely’ the precursor for miso, soy sauce, sake, mirin, and a whole host of other ingredients or had the thought, worrying to their family & peers that maybe, just maybe, simply letting some fish (& their entrails) ‘rot’ and deliquesce into the magic (yes, I’m using that word again) ingredient that is fish sauce, and then necking it, was worth braving a bout of dysentery or worse?

I’m going to write a much longer piece on kōji but for the moment, hear it described very simply…

…yet so vividly, by food scientist Ali Bouzari in Kara Platoni’s “We Have the Technology“:

The magic of kōji is that it’s a bunch of little happy molecular knives dicing up everything into small bite-sized pieces, so that there can be a greater chance it will be the right size and shape to fit into one of your receptors.

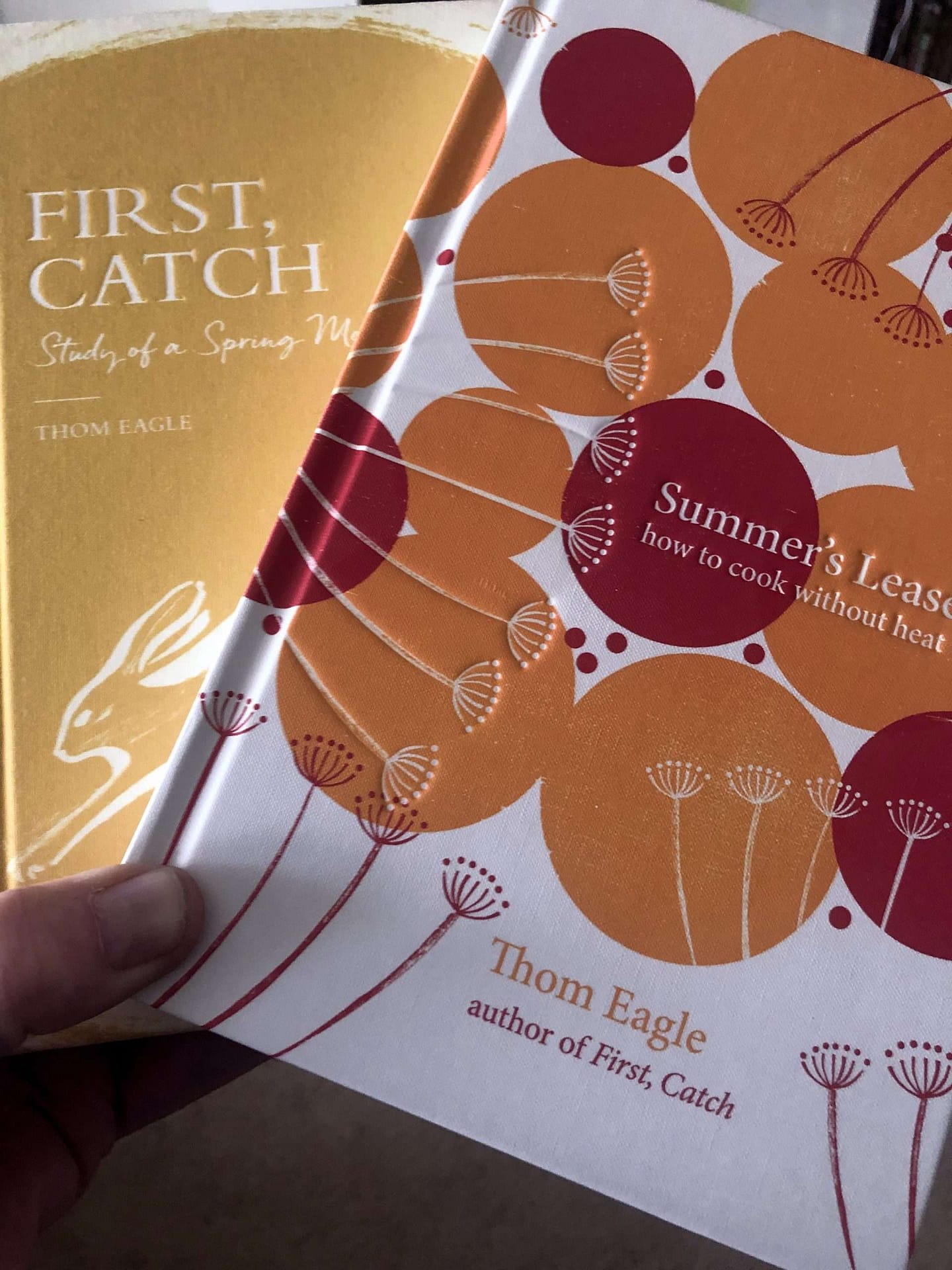

Cook and writer Thom Eagle has two books out (currently), the writing in both of which I really admire and which I take joy in re-reading…

…but it’s in his “Summer’s Lease; how to cook without heat” where he spends some 20 or so pages (10% by weight, no less) talking about ferments, but most importantly about the idea of cooking as a metamorphosis. This moniker applies — superbly — as a description of the end result of time, of the changed product after a ferment has taken place. Maybe not in the Gregor Samsa sense — although interestingly temperature plays an important role in insects that use metamorphosis for their development as each individual species are found to have specific thermal ‘windows’ that allow them to progress through their developmental stages. Have your ferment too cold and nothing happens; too warm and it barrels along too quickly. There’s a Cinderella’ porridge temperature band in which this process can best take place. Nature doesn’t waste a good idea.

The Japanese — along of course with the (generally) poorest from any other country, but I’m concentrating on this country for this piece — have always suffered through regular famines, crop failures, wars, rampaging rich people (sometimes called “the nobility” or “our betters”, but in reality, just the usual entitled criminals dressing up their land grab or battles for power and influence over similar fucking garbage-can fire humans, under the guise of some higher purpose that meant that either you had to die fighting for — or against them — or find that your own, limited, resources, the chicken, the family pig, the small garden of vegetables, were stolen by them for their troops, expropriation in a cause or for a fight, you had absolutely no interest in).

This meant that nothing could be left to be wasted. If “it” could be salted, pickled, fermented or otherwise transmogrified into something else, something that lasted, that you could put away (“put up”), safely, to be stored in the cellar, the pantry, even in pots outside in the ground, that then stopped you starving later that year, or the next, and that very understandable imperative, was what brought on these ideas: “innovate or die”…

I came across these salted squid guts on Twitter and of course needed to know more. They’re called Shiokara 塩辛 (translated as ‘salty-spicy’) and are made from various marine animals inc. squid in yet another process that involves time and patience. In this version, the raw squid are sliced and then served in a paste made from their viscera which have been mixed with about 10% salt and 30% of the aforementioned malted rice and packed into a close-able container and left to ferment for up to a month.

The flavour is described as similar in saltiness and fishiness to that of the beloved European cured anchovies, but with a different texture and yet even in Japan it…

is considered something of an acquired taste even for the native Japanese palate.

It was valued in post-war Japan because 1. other protein sources were scarce c.f. the earlier point about the effect of wars and, in this case, the US Army nicking anything that moved and 2. it didn’t require (pretty non-existent refrigeration) & today, still continues to be eaten as a rice condiment or as bars snacks, where it’s eaten in one quick gulp, one swallow, then followed by a whisky chaser.

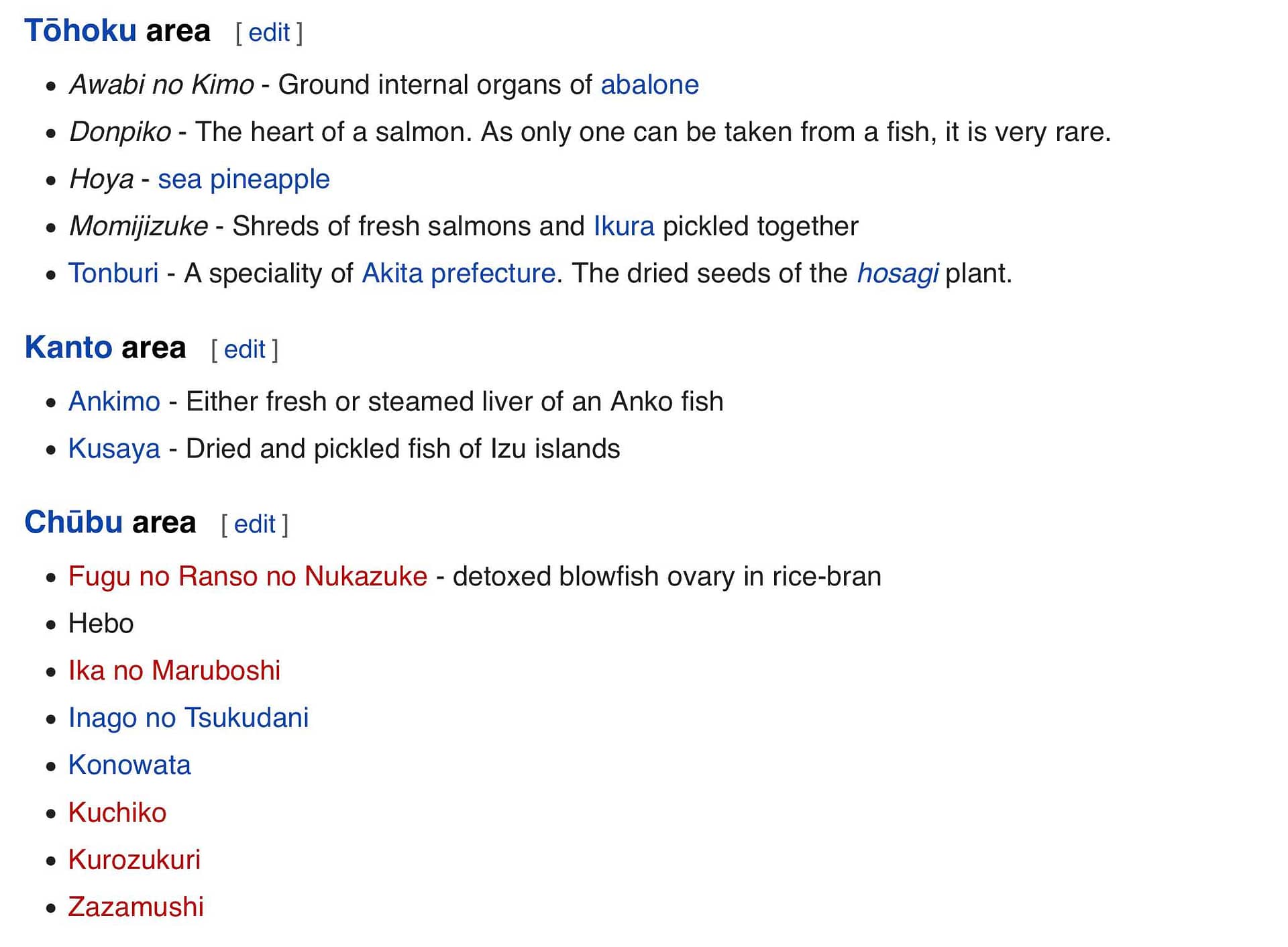

One of a member of group of food items that the Japanese calls Chinmi (珍味) (literally “rare taste”, but more accurately “delicacy”), which are (often hyper-) local food items that, in many cases, are now no longer popular or needed but that speak to the history and problems that each item helped to overcome.

Their Wiki page is another Alice rabbit-hole of investigation (I’ve copied a few here so you can see the variety) which means I’ve got about 20 open browser tabs, simply for these, which in turn lead to more tabs. There’s almost a fractal level of research needed here, where each word opens up to reveal an almost infinitely deep ravine of further words…

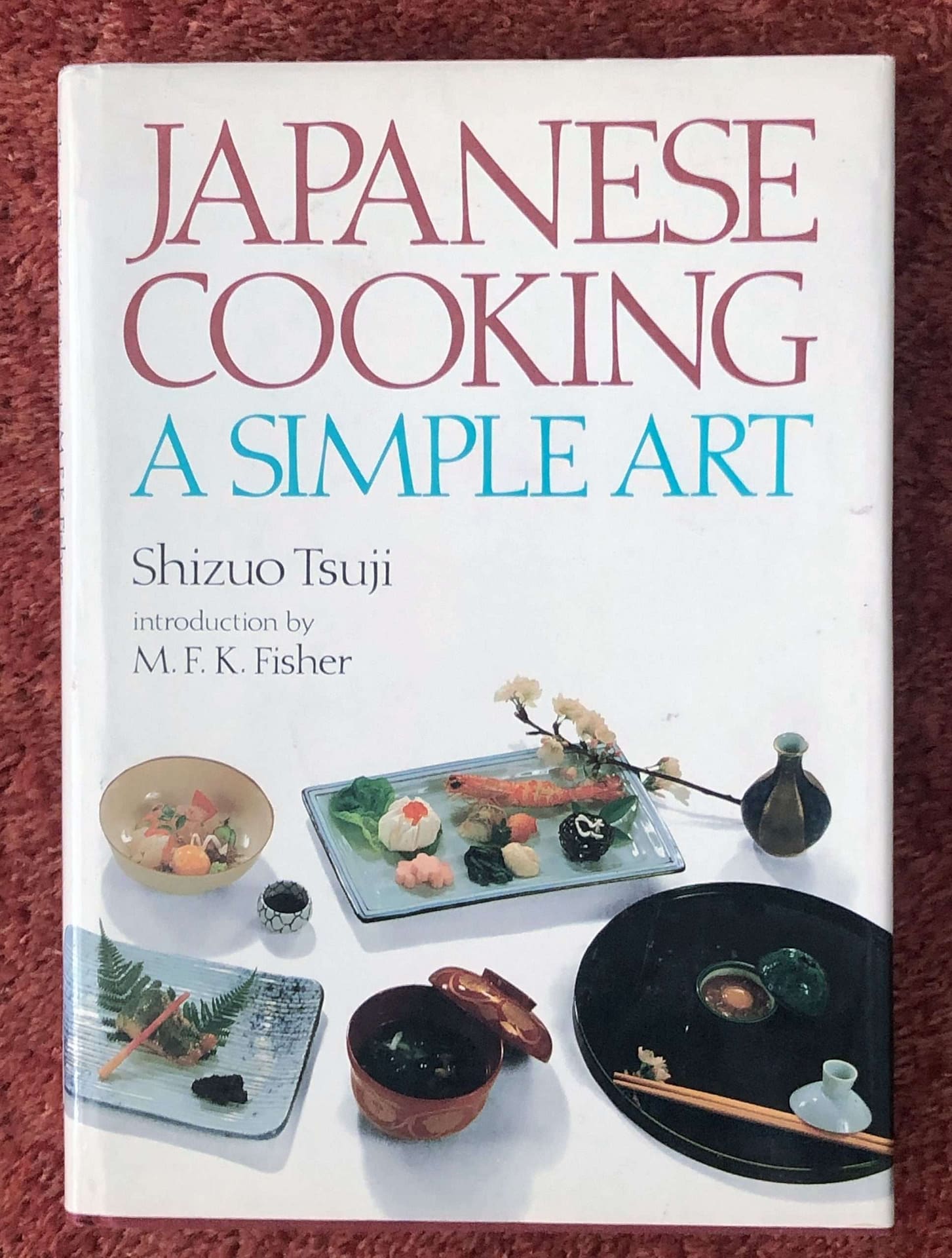

…many — if not most of them — needing pickling or fermenting to ensure longevity and the accrued storage benefits that brings. I can’t find any of them mentioned in the canonical “Japanese Cooking; A Simple Art” by Shizuo Tsuji but then he was writing a long time after the end of WWII; in a period in the 80s, when Japanese cooks were going out and demanding respect for their skills and cuisine from outside the country, most especially from Europe where he’d trained many foreign chefs, before going on to open his own cooking school in Osaka, so it’s hardly surprising that ‘peasant food’ — a plated reminder of a hugely painful episode for the Japanese psyche — wasn’t highlighted by his recipes.

There’s whole ecologies to digest from the chinmi offerings; I intend to do just that…

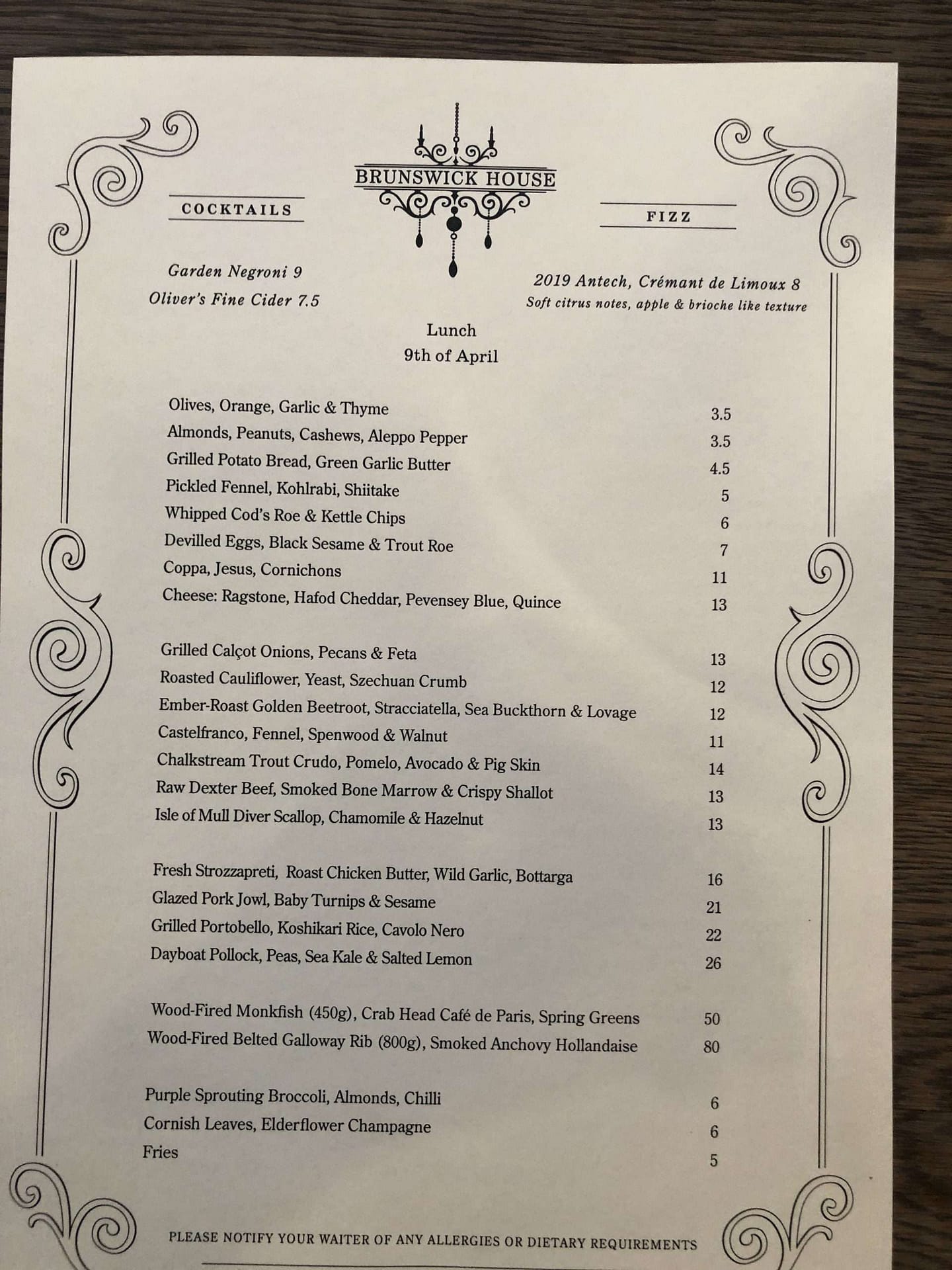

This month also marked the very first (and also by design, solo lunch) meal eaten at a restaurant since March 2020. The place I chose was Jackson Boxer’ Brunswick House in Vauxhall.

Many years ago — in a different economic reality — I used to work as the IT Manager for MacMillan Cancer Relief, just next to the building housing the spooks at MI6, which hadn’t long been completed. The rest of the area at that time, wasn’t much changed from how I remembered it looking in the 70s but it sure as shit is now, with rank after serried rank of apartments, towering over the Tube station and over the classical Georgian frontage restaurant — in places even blocking out views of the sun and the sky — thrown up to try and satiate the endless demand for places to help in the laundering oligarch and klep black money.

Rant aside, that the restaurant is surrounded — indeed almost now hidden by — all this shitty architecture detracted not one jot from the meal that I ate. My thanks to the team there, especially the Irish-accented woman with a fully inked right arm and the beardy French guy, both of whom were superbly great company and made this such a lovely venture back into eating out. We all agreed that the crab head café de Paris sauce needed to be bottled and sold separately. It would be great on anything. Gotta say that the wood-grilled monkfish it accompanied was totally banging and we bonded over the mutual suggestion of taking this sauce and slathering it liberally & with complete gay abandon over toasted muffins but there’s pretty much nothing actually that wouldn’t benefit from this elixir being added.

And finally, to tie this piece up into a neat bow and in a fine show of patience, my own world was therefore improved by both time and waiting. I had been more than a little concerned that the intervening 26+ months would have led to my taste-buds atrophying. They hadn’t. And patience prevailed.

Anyway, here’s the menu, which I did my level best to make serious inroads onto. I do need to go back though, to finish off the work…

I’ll leave you to work out which dish is which… Or, just book a table and go and find out in the flesh.