Until I read this 2021 Vittles London “What Is Kurdish Food” piece, I’d not (consciously) heard of Musa Dağdeviren. That’s on me of course, as he’s possibly the most famous extant Turkish chef — ‘the saviour of Turkish cuisine’, or so at least claims his publisher Phaidon — as well as the subject of a Netflix episode of ‘The Chef’s Table‘ which I do recall seeing him in, yet still his name didn’t register. And again, that’s on me.

I’m white, English, and over 60 now — indeed, Musa and I are almost exactly the same age — but as a family, pretty much everywhere we lived after leaving central London, we only had to cope with spelling and pronouncing the likes of Smith or Jones, Littlewood or Robinson with maybe the occasional Farquason-Dead-Leg-Puckle (or similar aristo bollocks) thrown in.

Our nation’s colonial and imperial history makes us arrogantly lazy. We don’t take the time to listen. Well, not all of us are guilty of that, maybe, but sufficient of us that still, so many people, friends, neighbours, colleagues, those with names & accents (verbal and in their lettering) that don’t fit into the very narrow “English” track — even Gaelic, Welsh & there still are around seventeen languages native to the UK, for fuck’s sake — continue to have to waste far too much of their time trying to get them pronounced & spelt correctly. I mean. It’s. Not. That. Hard…

There’s Google Translate and so many online dictionaries that allow anyone to make a good fist of pronouncing (appropriately, sensitively) any word they could come across. There’s no excuse (except indifference or malice) for any longer mangling things so horribly.

(That he looks a little bit like Eric Clapton in this photo, isn’t his fault. Sooner one Musa in this world than a 1,000 racist Clapton’. Eric really is and was an odious man)

Anyway, back to Musa who was born in Turkey yet of Kurdish background, and was 20 when the military coup took place in 1980 which he says impelled him to start reading and from that:

To live in a society, you must choose a side. So I decided I was going to fight for the things I believed in.

He went on to setup a bakers’ union in his home town of Nizip, Gaziantep, became a master baker & kebab expert, brought them all out on strike for 40 days & secured the pay rise he’d promised them…

I had a strong political stance & I was able to express it but after the bakers strike there were real threats to my life, so I had to flee my home town

…to Istanbul, worked for his uncle’s restaurant then was obliged to undertake the compulsory Turkish military service in the catering corp, where he (taking his life in his hands I’d have thought) told his boss that they were doing everything wrong and promptly went on to show the team of 6 how to how to cook properly for 2,000 odd soldiers in the regiment…

so that people came back and asked for seconds, there was no food wasted and people started complaining there wasn’t enough food

… and eventually then setup his own restaurants in Istanbul and his foundation now supports the work he does in producing the research related to his rural “food anthropologist” projects.

And then here, right here, in this nuanced piece by Jonathan in a talk with Melek Erdal, a Kurd, they jump straight in to attempt to un-mix this melting pot, to explain and breakdown the reasons & causes behind the long, long tempestuous history of this region and the peoples, that make up (at least part of) Anatolia.

As Musa Dağdeviren, a chef with both Turkish and Kurdish heritage (who does not identify as Kurdish) reminds us, food has only geography, not ethnicity. And yet, to label food as ‘Turkish’ is uncontroversial; to call it ‘Kurdish’ is somehow political.

I’m not even going to try and say any more about this area, the inhabitants; I don’t have any knowledge, any background and I’d simply make a complete & utter cock of myself — stop laughing at the back there, thanks — as well as almost certainly inadvertently deeply offending many people, in even attempting to summarise or précis the hundreds of years and hundreds of thousands of people whose interlinked story this is, which has brought us to where we (and they) are today. It’s for others, those who’ve lived this, are part of it, those experts (and yeah, fuck you Gove) that you should seek out.

Buuuuut… the stories, the food, the recipes, the descriptions reminded me vividly of one of my next door neighbours (many years ago), an Armenian man, first name Simon, last name sadly forgotten, whose geographical proximity, similarly convoluted and complex centuries and my taste memory, make them all seem almost coterminous.

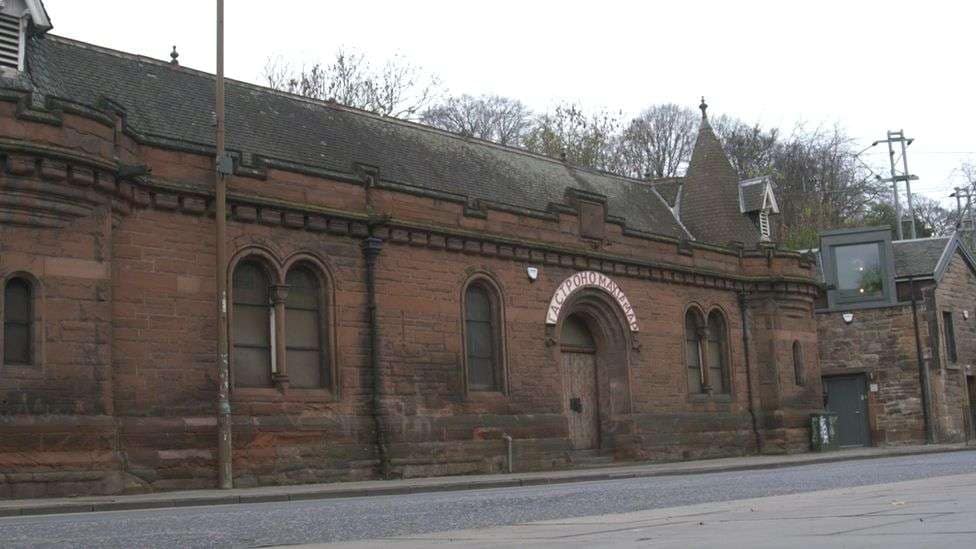

Whilst reading around for this post, I came across a curious article, the mystery of “Whatever happened to Peter the Armenian cook?” and his Edinburgh restaurant called “Aghtamar Lake Van Monastery in Exile”, described as

part exotic dining, part eccentric performance…

which you should probably spend a few minutes reading as well.

Like this Peter, Simon (widowed as he was by the time I knew him) wasn’t a trained cook but a second generation immigrant, simply cooking for himself and serving the family dishes he had grown up with; having come to England with his parents, who were fleeing the Armenian Genocide of the early 20th Century.

And serve he did. To his huge extended family who visited pretty much every other day, loud, laughing, full of life, their children, his grand & great-grand children, spilling out into the small garden, bouncing around, weather ignored.

And to me. A grateful beneficiary of pots and dishes, full of red, iridescent oily, rainbow hued & glinting sauced meats and pulses and spiced, hot, hot, hot peppered plates of rice, tucked underneath other kitchen-foil wrapped delights.

Left outside my back door — which I’d find when I came home from work — or handed over the low fence between our two gardens at the weekend, by him or one of his daughters or sons or in-laws. It was impossible to keep track of them all. I just remember their smiles. Which smile I mirrored, grinning — almost certainly inanely — because his food was so good. So much fun. All I had to do was eat it, marvel at tastes, textures, spices and then clean the dishes, return them over the hedge or place them back on his doorstep and — almost magically — they’d be refilled and sent back to me at some point, over the 3 or 4 days or so.

I’m not sure I was the best neighbour he could have had. I was happy to eat the food he’d share with me yet I only managed to make a few ‘British’ things to hand over the fence to him (spag bol, stews, a curry or two) which he, kind, friendly man that he was, claimed he enjoyed immensely. And the occasional bit of flower-bed digging or help with grass mowing. But more interested in my ‘career’ then, than in community — selfish, and lazy really — I confess to not always going outside if I saw him in his garden, fearing being trapped there for an hour as he reminisced. Not that it wasn’t often interesting, just “I didn’t have time, at the time..”

For being sometimes less than gracious, for being less of a friend and neighbour than I could and should have been, my apologies Simon. I hope you weren’t too disappointed with me. Your food is still a great memory, so you live on, if that’s a consolation.

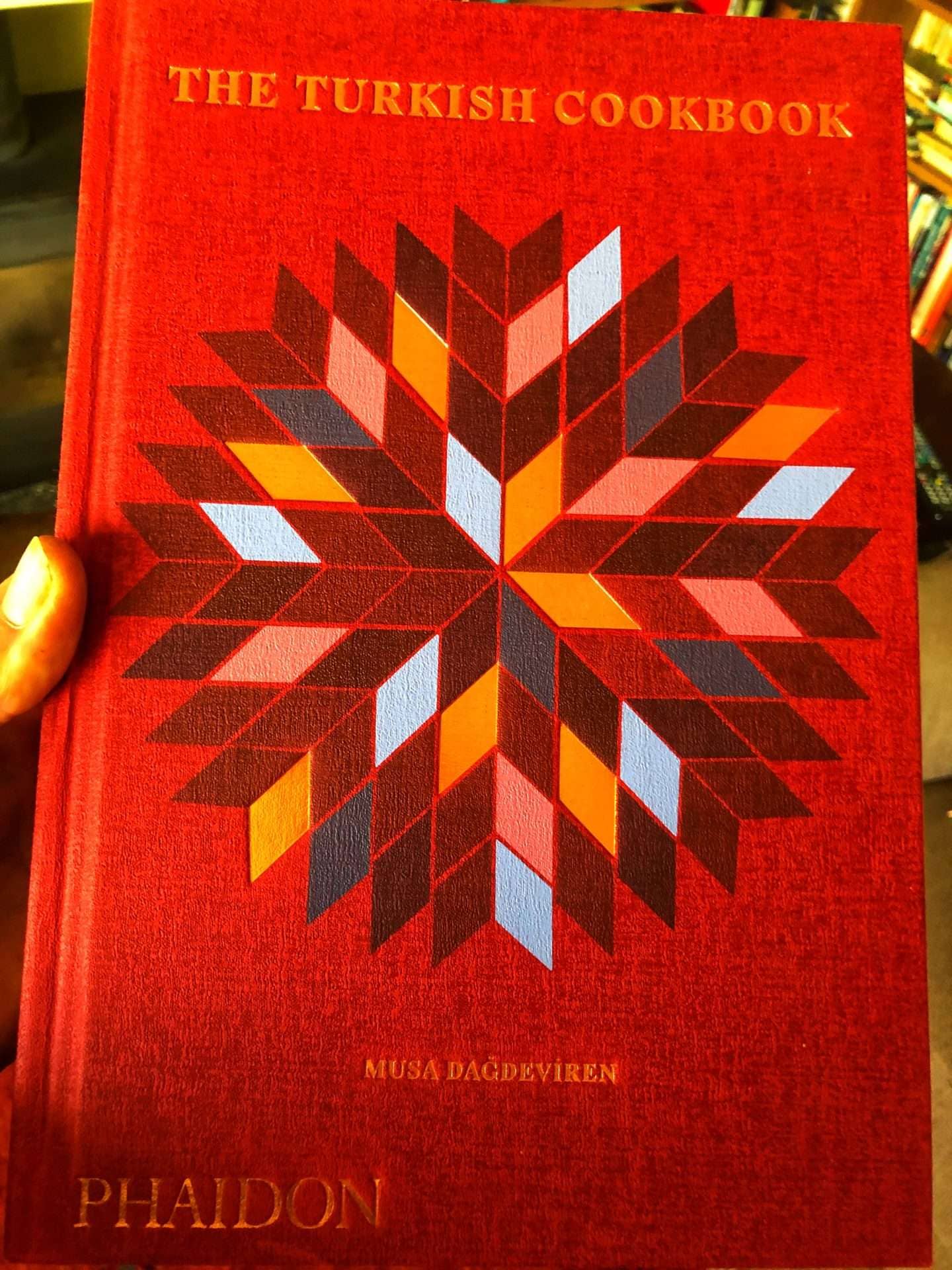

After that meandering history lesson, let’s (possibly with a sigh of relief) drag you back to Musa & his “The Turkish Cookbook: The Culinary Traditions & Recipes from Turkey”.

A real heavy weight this, coming in at 1.8kg & 550+ recipes with what to me, seems a panoramic and hugely comprehensive tour around his country and the home food from the poor…

A rich person can buy what they want. A poor person makes their wealth by means of creativity.

…in the villages and little towns that he loves, cares about, espouses & is trying so hard to preserve.

We must acquire the traditions from the carriers of our culture and celebrate our rich diversity in a way that unites us.

One urgent reason for this need to preserve them, is that so many of the dishes and recipes didn’t come out of restaurants and cafes; thus weren’t made by men, so his ‘cultural ambassador’ role as he was described in the Netflix show, depended on him going out, taking to, watching and then capturing these (usually only) oral traditions via the women in the house.

He goes on to say:

stews are considered home foods.

Simon definitely agreed with this viewpoint. Stews & casseroles were his main go-to dishes, so I’ve tried to find one that, at least for me, reminds me most strongly of the type of plate that he’d offer me, and I’ve chosen Horoz Etli Güveç (or Rooster Hot Pot). This comes from around Adana, in the Mediterranean Region.

Preparation time: 20 minutes Cooking time: 1 hour 20 minutes Servings: 4

Ingredients :

2 kg small roosters, meat only, chopped into 2 cm pieces

400g potatoes, chopped into 2 cm pieces

1.5 kg tomatoes, chopped into 2cm pieces

3 garlic cloves, peeled

2 tbsp. red pepper paste

1 teaspoon dried chili flakes (red pepper)

1 tablespoon dried oregano

200 ml olive oil

Directions:

Preheat the oven to 180 degrees Celsius.

Mix the rooster meat, potatoes, tomatoes, peppers, garlic, red pepper paste, dried chili flakes (red pepper), dried oregano and olive oil with 1 ⁄2 tsp black pepper and 1 tsp salt in a large bowl for 3 minutes.

Transfer the mixture to a saucepan or casserole disk. Bake in the hot oven for 70 minutes.

Transfer to serving platters and serve.

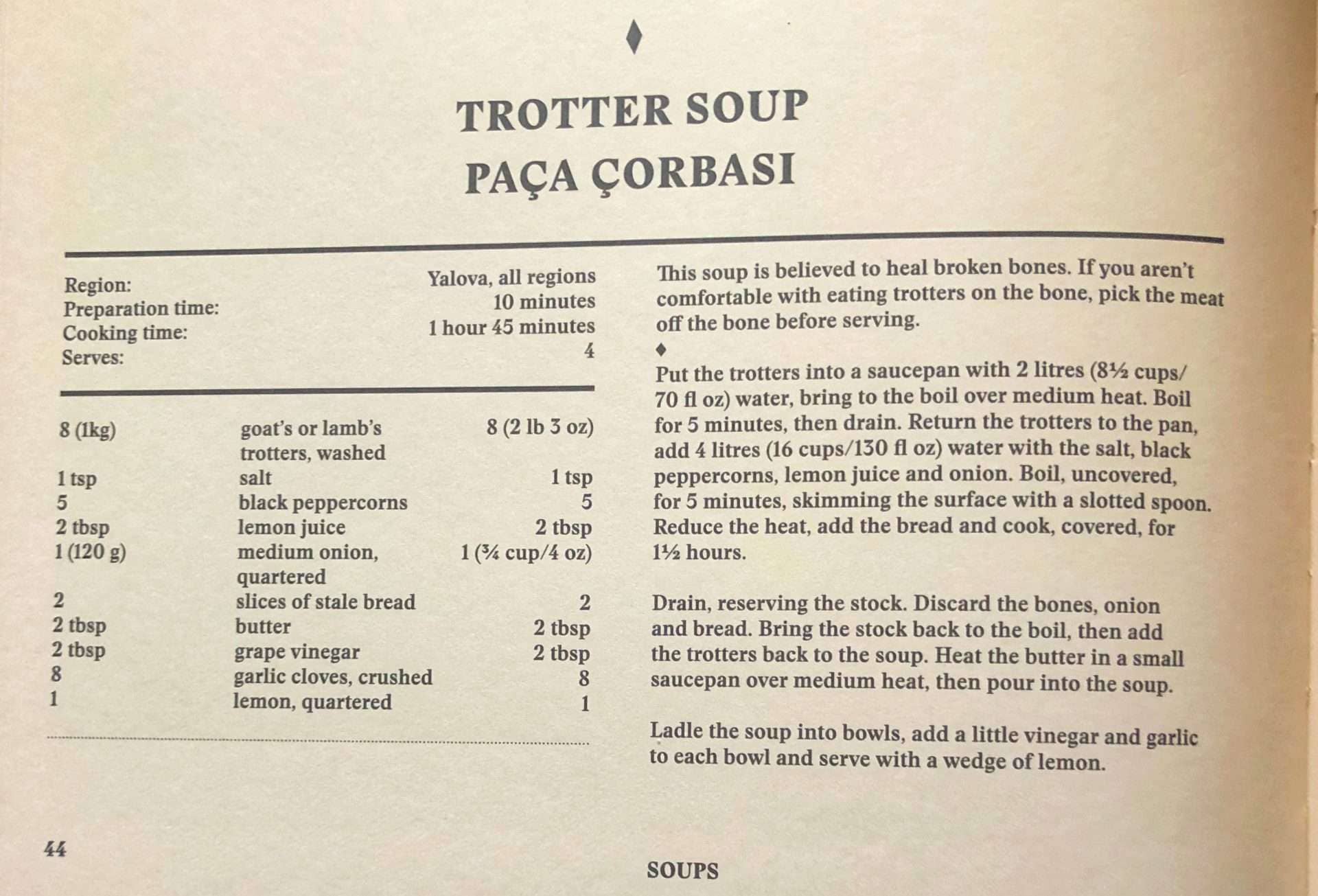

Of course, I had to finish up with one of Dağdeviren’s offal dishes “Trotter soup or Paça çorbasi” though; because as he says

Trotter soup comes to the rescue every time we have a broken bone (even the doctors are in consensus that this folk remedy really works.)

And finally, I’m not sure, even now that I totally got everything going on in the film “Once Upon a Time in Anatolia” but I vividly recall the meal the central characters take with the small-town mayor. One of the central scenes in the film with as always, food & the eating of food anchoring, underpinning, quotidian, even for those of us whose job forces us to search for a corpse…